My Research

Transformed Human Rights Geographies Over Time

A central theme in my research is how human rights dynamics and politics have changed over time. within the Middle East and in relation to the Middle East.

In After Abu Ghraib, I examine the change and continuity in human rights dynamics and the power relations embedded in them, in the United States, the Middle East, and between the Middle East and the United States following 9/11. For example, the book lays out the partial reconfiguring of global human rights’ politics of the era created by unprecedented mobilizations, challenges, and critiques directed from the Middle East to the United States, in contrast to the almost exclusively West to East traffic of human rights that had existed prior to the era.

In later works I examine how the Arab Uprisings further upended the Middle East’s human rights landscape. For decades, "human rights in the Middle East" had been a subject of scrutiny, debate, and mobilizations spearheaded from outside of the region. Western governments, including successive US administrations, frequently took up the region’s dire human rights conditions and funded a variety of human rights initiatives to remedy them, in many ways as a substitute for forgoing economic and military alliances with highly repressive regimes. These foreign governments’ human rights talk was heavy in its emphasis on women’s rights and other violations for which backward cultural and religious beliefs were designated as the key culprits and light on its emphasis on civil and political rights violations. At the same time, local voices promoting human rights were largely silenced by authoritarian rulers simultaneously paying lip service to human rights and undermining it by arguing that it served foreign, Western, imperialist agendas. Cumulatively, these dynamics resulted in minimal Middle Eastern agency in defining the nature and scope of its own predicament vis-à-vis the human rights paradigm.

The 2011 Arab Uprisings not only resulted in a sizable rise in popular rights consciousness and local human rights activism, the region’s human rights politics came to be increasingly driven and defined from within the Middle East, not abroad. Thus, despite the Arab uprisings’ dark turn, important inroads towards upending some of the most longstanding and problematic aspects of the politics and geography of human rights vis-à-vis the Middle East materialized.

Currently, I am considering how mobilizations of the last half decade continue to transform the Middle East’s and global human rights landscapes.

Varied Middle Eastern Experiences of Human Rights

In recent research, I argue Middle Eastern and marginalized non-Western populations’ interactions with human rights are complex and varied.

These populations’ dispositions towards, and the meanings they accord to human rights often stem not just from how they evaluate the human right framework’s content as Is often assumed, but also from their experiences of, judgements on, and emotional reactions to the morality of the practice of human rights unfolding around them.

In my latest publication “Human Rights as Mockery of Morality, Manifesting Morality, and Moral Maze” in the Journal of Human Rights, I have developed a typology of these experiences drawing from and applying the typology to primarily to contemporary Egypt.

I am now working on research in which I apply the typology to the case of Iranian and Iranian diaspora mobilizations spurred by the Killing of Jina Mahsa Amini and the ensuing 2022-23 “Woman, Life, Freedom” Protests.

Human Rights as Mockery of Morality

As mockery of morality, cumulatively a power-laden politics and practice of human rights are widely experienced as flying in the face of the framework’s moral promise. As a result, human rights talk is collectively judged to be a light and patently corrupted instrument deployed disingenuously by various elite and powerful actors in ways that not only fail to challenge abuses of power and injustice, but instead primarily bolster and reproduce them. Human rights activists and the discourse they employ thus become associated with the absence of integrity, genuine moral commitments, and a real will to disrupt the status quo enough to bring about substantial change.

At the same time, marginalized populations are highly conscious of their exclusion from the framework’s emancipatory promise. Human rights are as a result, experienced as unmistakably performative and imbued with appalling moral contradictions, the operation of power in plain sight rendering its asserted moral vision a farce. When experienced as “mockery of morality,” human rights is alienating and fosters a sense of injustice exacted not only by abusive actors, but by the human rights framework itself, producing widespread cynicism.

While I argue that the era also encompassed important inroads away from it, in many critical respects, the Post-9/11 era epitomized experiencing human rights as mockery of morality.

The cover of my After Abu Ghraib (which is not about Abu Ghraib, but about the human rights politics it inaugurated), encapsulates human rights as mockery of morality. On the one hand, the denials of dignity of American “War on Terror” violence are unmistakable. On the other hand, the pictures are part of Iranian state-sponsored street propaganda, illustrative of the Iranian state’s co-opting of the West’s power-laden human rights deployments.

Human Rights as Manifesting Morality

Marginalized populations can also experience human rights in a diametrically opposed form, that of manifesting morality. In this form, human rights is experienced as a politics of conviction imbued with moral weight, epitomizing pure, genuine, faithfully moral action and intent. As such, human rights can be adopted as an idiom that lays bare and articulates a meaningful challenge to the immorality and injustices of the status quo. Key deployments of human rights could be widely experienced as being born out of and attuned to the local populations’ various struggles. While those performing human rights persist, a human rights practice embodying ethical commitments and challenging structures of power in ways widely recognized as genuine and honorable moves to the fore. The coherence in human rights’ emancipatory promise and moral practice in turn render it a compelling avenue for articulating a desire for greater justice, dignity and new morally-guided social, political and economic orders.

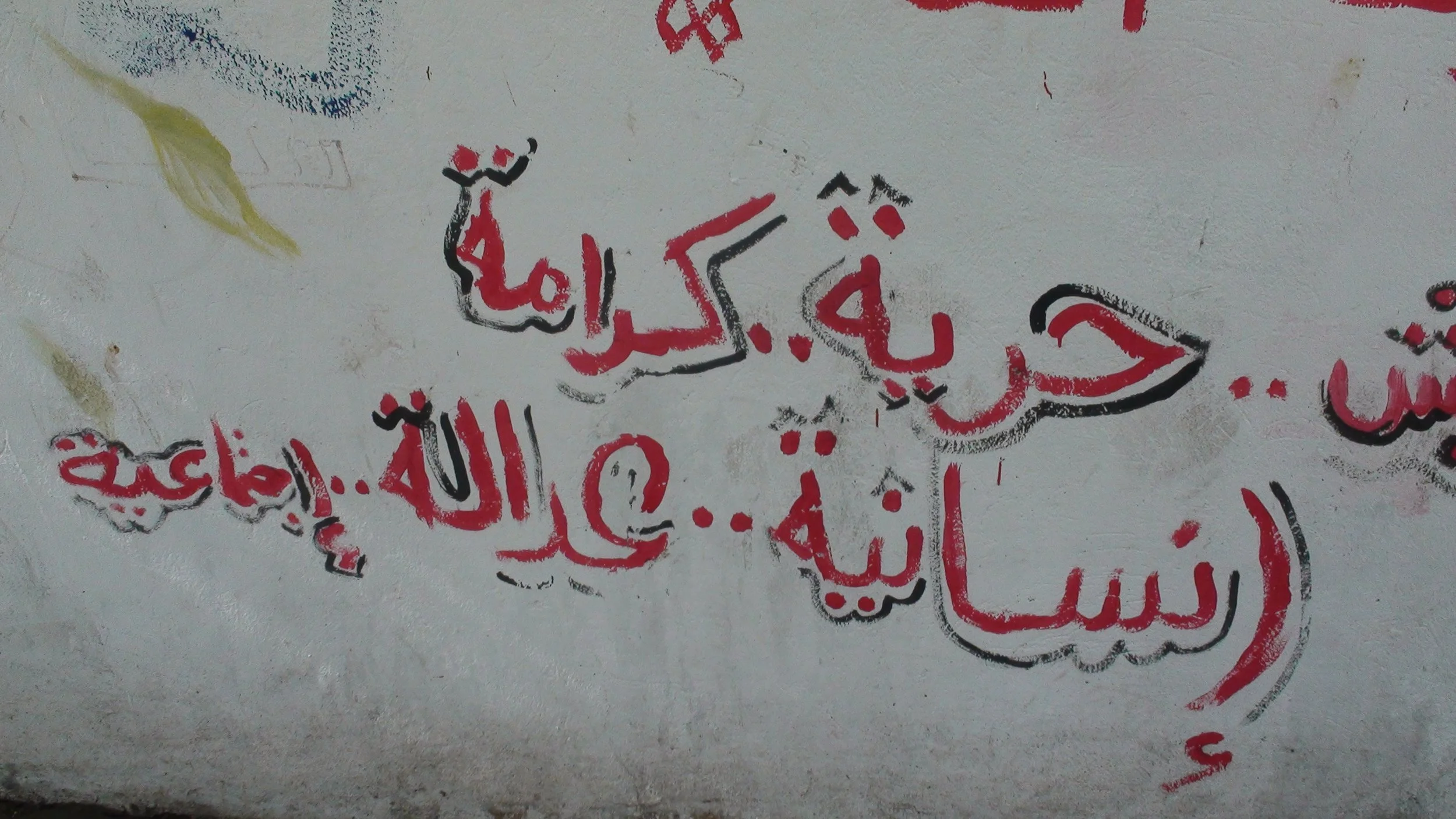

This can be seen at the height of Egypt’s 2011 Uprising and beginning of its ill-fated political transition. The photo here is of wall graffiti I encountered in Cairo in the summer of 2011 reading “bread, freedom, human dignity, and social justice”.

Human Rights as Moral Maze

In the experience of human rights as a moral maze ordinary people are bombarded by a flurry of human rights claims and counterclaims, many of which are strategically deployed by powerful actors to muddy the waters but are not readily identifiable as such, fragmenting popular dispositions towards human rights claims. Parts of the population adopt hyper-partisan human rights stances while others find the muddied terrain produced by a whirlwind of accounts of human rights violations and challenges to the credibility and sincerity of those accounts or the activists posing them too difficult to evaluate as either manifesting morality or morally corrupted. Thus, the moral maze experience departs from the other two experiences in that human rights politics while ubiquitous, is endlessly contested, often preventing a broad consensus among the population on the moral positioning of its practice. While hardly new, human rights experienced as moral maze has grown exponentially with the rise of social media and the polarized, post-truth, misinformation and disinformation political sphere it is both a product of and for which it can be a catalyst.

Mapping Iranian Human Rights Engagements, Politics, & Struggles

My research and thinking about the human rights dynamics of Postrevolutionary Iran spans two and a half decades.

During the time of the 1997-2003 Khatami/ Second of Khordad Reform Era, I examined Islamists’, post-Islamists’, Islamic Feminists’, and marginalized secular forces’ rights-based discourses, debates and framings of rights claims using Islamic and postrevolutionary discourses.

Subsequently, in conducted a study of responses from the Green Movement’s de facto leaders, "dissident clerics’, jailed activists, and ordinary Iranians to the Iranian state’s brutal crackdown on the 2009 Green Movement.

Withe the unfolding of the stunning “Woman, Life, Freedom” protests spurred by the state killing of Jina Mahsa Amini, Iran has returned to the fore of my research, now centered around two primary lines of inquiry.

One project places the Iranian case into the mockery of morality, manifesting morality, and moral maze categories of the Marginalized Popular Experiences of Human Rights Typology developed, with the goal of identifying ways the case corresponds to, diverges from, and expands the theoretical insights of this typology. In the process, it aims to provide a rich composite of the many forms, manifestations, and layers of the “Woman, Life, Freedom” human rights politics that unfolded in the wake of the killing of Jina Mahsa Amini.

A second project put forth through an article titled “The Reverse Savages-Victims-Saviors Metaphor of Human Rights” (in progress) focuses on how international human rights politics can eclipse local populations’ experiences of subjugation at the hands of regimes like Iran’s asserting victim status within the international sphere. Specifically, it argues that imperialist and power-laden human rights politics epitomized by traditional savage-victim-savior constructions frequently give rise to a reactionary progressive politics which denies local populations’ agency by according victim status to regimes asserting anti-imperialist or religious identities, treating this “victim state” as synonymous with the population it rules, viewing these populations’ suffering almost exclusively through the dehumanizing lens of geopolitics, and ultimately succumbing to its own progressive/ reverse victims-savages-saviors metaphor of human rights.